Since Dr Ian Player and Magqubu Ntombela started the Wilderness Leadership School in 1957, over 70 000 people worldwide have been through it. The courses have subsequently become broader and include a wide variety of activities.

This 1967 article in the Natal Wildlife magazine traces the school’s humble beginnings.

Wilderness School Trains Leaders.

For a long time, conservationists have been alarmed at an education system which fails to give students an awareness of the most urgent of the country’s problems, soil erosion. School biology lessons cover only the rather complicated studies of anatomy, physiology and microbiology and the child leaves school without much interest in nature.

Yet South Africa is threatened with a “gloomy and ghastly future”.

Almost 50 years ago, a Government Drought Investigation Commission warned the country that the logical outcome of South Africa’s abuse of her soil was “the great South African desert uninhabitable by man.”

Since then, the desert has continued to advance, the warnings have continued to echo, but the ordinary man has not noticed or heard. The food-producing soils are flowing away to the sea while the population is exploding. More people to feed off less and less soil. Education is the only method of stirring the nation. And education is tragically lacking.

ATTEMPT

However, in Natal, an attempt is being made to train senior schoolboys of leadership calibre to understand that man’s survival depends on well-conserved soil, vegetation, and water.

This pioneering project to “educate in the field” is known as the Wilderness Leadership Course.

The idea was born in 1957 when lan Player, now Chief Game Conservator of Zululand, took a group of schoolboys on Lake St. Lucia. A few days among the birdlife, hippo herds and crocodiles, and fish gave the boys an experience they had never had before.

A few more groups followed, and in 1960 Ian Player decided to form a school.

By 1963 there was sufficient enthusiasm for a proper Trust. Colonel Jack Vincent, then Director of the Natal Parks Board, approached Mr Frank Broome (ex-Judge President of Natal), who in turn approached Mr T. J. A. Gerdener, the Administrator of Natal, and Dr Busschau of the Chamber of Mines. Mr Stanley Osler and Mr A. 0. Simpson were also asked to be Trustees. This special trust was registered in 1963.

FUTURE LEADERS

This school is not designed for mass education. However, it is the most effective present method of “getting the message across” to boys who show particular character and personality and academic achievement, irrespective of their future field of work.

Later it is hoped these young leaders will help guide opinion and thought towards conservation problems. Since the school was established, several courses have been held.

The course always starts at Pennington Park, on the farm of Mr Ian Garland, at Mtunzini.

FIRST LESSON

Here the boys have their first lesson, a talk by Mr Garland on the beginnings of the world and evolution. On a walk around the Park, they are given a picture of the interdependence of nature. This prepares them for the experiences and observations of the days to come.

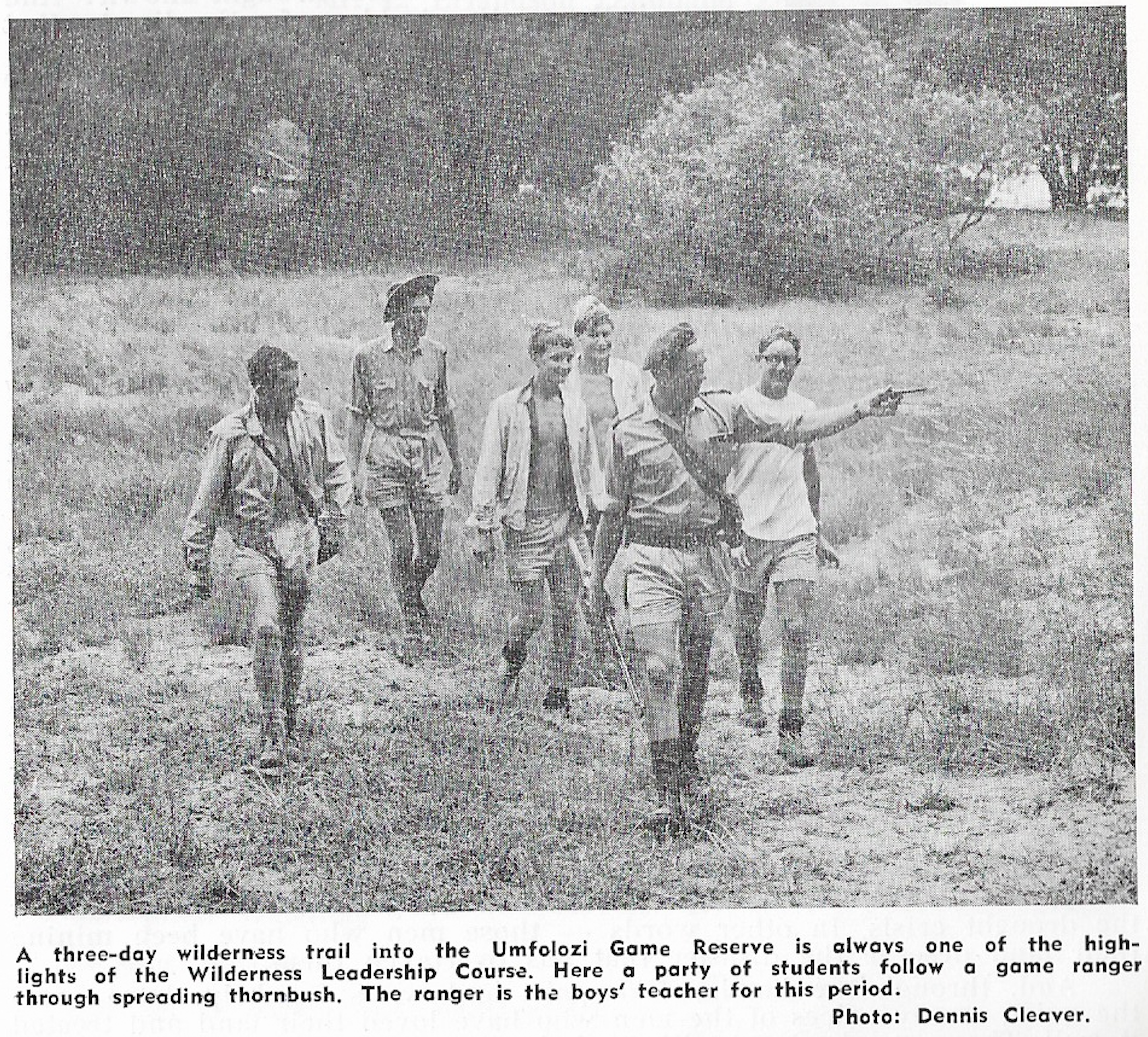

The second stage of the course is at Umfolozi Game Reserve, where the boys spend three days on Wilderness’ Trail Trekking among the kopjes, bush and rivers of the Reserve; they learn about the game and the long history of man’s association with animals and growing things.

For many boys, the information that wildlife and wild country can be economic resources is a new thought. This first taste of wilderness is always the highlight of the school for the students.

From Umfolozi, the boys travel to a different environment, Lake St. Lucia.

A Senior Ranger guides the boys around the lake. While on canoe trips, land trips or walks around the lake edge, they study the delicate balance of saline and freshwater life, the aquatic birds, reptiles and mammals in this rich biological storehouse.

Once again, there is an experience of wilderness for them. They visit the Lake’s northern wilderness section, and in the dawn and sunset of a day, learn to appreciate that “time for reflection” is as basic a need for modern man as sleeping and eating.

FINAL STAGE

The final stage of the course is a hike from Lake St. Lucia down the Zululand Coast back to Pennington Park. For this part of the course, they are on their own and have to fend for themselves.

Finally, round a campfire on the last evening, there is an “indaba” to discuss the experiences of the school. Usually, men who manage the course guide and help these final discussions.

When the boys get home, there is still a report to be written on their impressions.

One youngster summed up: “The best way to teach the average man the very real problem of soil erosion is to show him, in the field, what is needed, and what it is like to see a strip of land that has not been maltreated by man.”

PLANS

The course is at present designed for six boys for a period of eight or nine days. However, the organisers are keen to subject over 100 picked boys a year to these lessons in character and leadership, soil and game conservations.

Mr Carl Erasmus, chairman of the School’s Management Board, has stated that as the school is not to be restricted to school-going boys, and as it is dedicated to the study of game and soil conservation under all headings, there is obviously no end to the good that it can do.

“The present drought conditions in South Africa have forcibly brought home the need for more

people in positions of authority in all walks of life to have a background knowledge and understanding of these matters,” Mr Erasmus states.

‘The main idea behind the creation of this school is to have as many future leaders as possible in this country introduced to these problems and impressed with their importance. By putting even a small proportion of the youth through this course, we are convinced that we will be helping the future of South Africa.

“At the moment we want to improve these facilities and want them established on a permanent basis.

“There is no reason whatsoever why the School could not operate throughout the year, incorporating other areas and reserves, and developing new aspects that can enlarge and improve the objects of the School.”