Sustainable use is the utilization of any resource that does not lead to its long-term degradation or depletion, thereby maintaining its potential to meet the needs of not only the resource itself but the current and future generations of people and other living organisms who do or could depend upon it. The animal rights movement completely opposes sustainable use. For example, the PETA India website specifically states, “Animals are not ours to experiment on, eat, wear, use for entertainment, or abuse in any other way.”

Manipulative language that may lead naïve readers to believe that any use of animals is entirely negative. Spitting in the face of sustainable use, so to speak, and the people who share landscapes with wildlife and other valuable, renewable natural resources.

These attitudes disrespect, devalue, and illustrate contempt for both humans and non-humans whose lives and livelihoods could be improved via sustainable use programs. A perfect example of this is the prohibition of the edible nest industry in India. (For a description of this industry as practiced legally elsewhere in southeast Asia, see The Conservation Imperative article, “Good Spit”.)

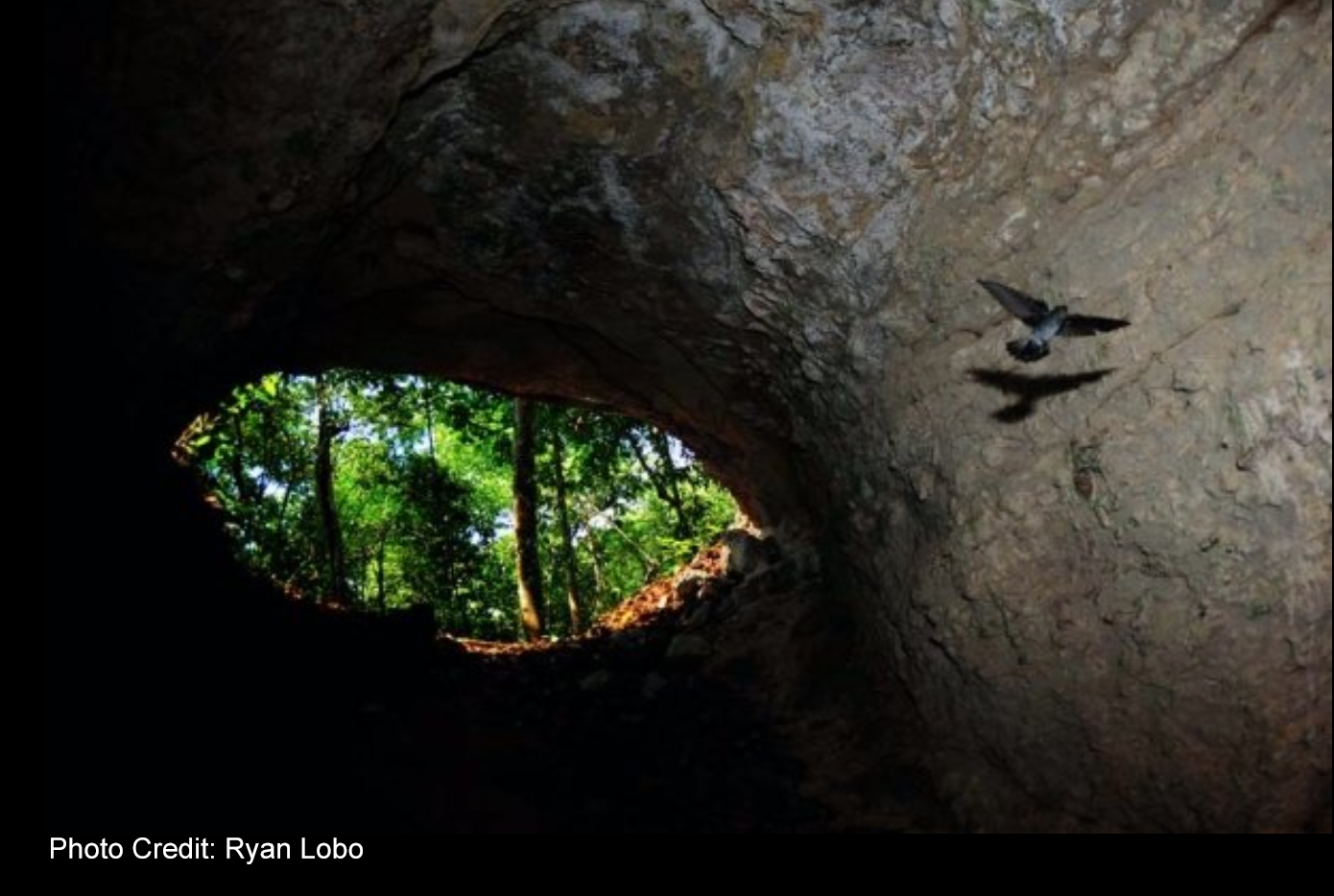

India’s government policies are influenced by the animal rights ideology that does not allow the consumptive usage of wildlife (besides fish and insects) and therefore does not permit this industry constitutionally that is thriving in other countries. The Andaman and Nicobar Islands of India are the western extremity of the range of the edible nest swiftlet, which produces these nests solely with their saliva.

Although this species of swiftlet Aerodramus fuciphagus is widespread and considered of least concern by the IUCN, the subspecies inexpectatus inhabiting these islands is endemic and marked declines in its population (80%) in this archipelago have occurred since the 1990s, leading some ornithologists to predict that extinction of this subspecies could happen soon if no measures are taken. Nests have been collected from these islands since the 18th century and can be done sustainably when properly regulated.

But India’s Wildlife Protection Act of 1972 made disturbing any bird nests illegal and prohibited wildlife trade. More recently, this, plus additional amendments, has had the crippling effect of driving any nest harvests into the illegal, unregulated, unsustainable realm.

Although these birds can re-nesting several times each breeding season if their nests fail or are removed, enough pairs must be allowed to raise one nest to completion each season to recruit young birds into the population adequately. Nest collectors who had the legal ability to harvest nests were operating this way and only taking nests that did not have eggs or nestlings yet.

But when only poachers can profit from any resource, the take is not regulated, no investments or efforts are made to protect the resource long term, and anything that can be taken is grabbed. The prevailing attitude becomes – if I don’t, someone else will. Nests of all stages and contents are taken, even, in desperation, ones that are only a few days old and a few mm thick, able to be scraped off the cave wall with fingernails alone.

Harvests may be as frequently as twice per week. The typically tragic scenario that results from a desired wildlife product having no legal value. A free for all with no concern for the future.

These remote, largely unpopulated islands are the entrance to Malacca Strait, one of the world’s busiest shipping routes. A perfect scenario is enabling poaching.

On just one island, Baratang, 60% of the 152 known nesting caves now host no edible nest swiftlets because of unregulated, illegal collections. Additional ecological impacts can be significant even when caves are not fully abandoned. Prolonging nesting by continually taking nests can result in chicks fledging in the southwest monsoon season, when the inclement weather and decreased insect food base impact their survival rates.

Swiftlets and bats also compete for cave space and cluster with conspecifics. Therefore, a reduction in one species results in that space being occupied by another.

In the Nicobar Islands, entire walls of some caves that were once covered by edible nest swiftlets are now occupied by white-bellied swiftlets (whose nests are too impure to have value) or bats.

In recognition of these problems and declines, a special Conservation Action Plan was employed in India during 2001-2008. Local Forest Departments employed nest collectors to protect and monitor nests until the end of the breeding season, allowing harvest only after they had fledged one brood. In protected caves, such regulations increased these birds’ populations in the Andaman Islands by 39%. Unprotected cave populations decreased by 74%.

Just as in any other sustainable use scenario anywhere around the world, if people (especially locals) are legally permitted to derive value from wildlife in a regulated way, they will protect it and take their roles as stakeholders in that resource’s future seriously. Some of the funds generated from such programs can also be funneled into anti-poaching efforts, research and management needs.

But this program was abandoned, presumably due to the prevailing attitude of those in power in the government, such as Maneka Gandhi, who not only has strong ties to PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals) and HSI (Humane Society International) but is a founder of the Indian animal rights organization – People For Animals.

In an April 11, 2016, Firstpost column in the journal of Beauty Without Cruelty (BWC), titled “India should be wary of the Chinese threat to its wild”, she states that the demand for bird’s nest soup and the fact that China views wildlife as a resource to be developed and used is driving these birds internationally to extinction.

Untrue.

Globally, the species is considered of least concern by the IUCN. The seemingly unstoppable demand for these nests has promoted a thriving legal industry that harvests nests both from the wild and from swiftlet houses in sustainable manners. Plus, it has led to the acknowledgement that more conservation efforts due to harmful agricultural practices and deforestation are needed to protect the insect prey species these birds and many other insectivores require.

She acknowledged in this article that the aforementioned study that her own country did enable swiftlet chicks to safely reach maturity, thus helping the species survive whilst also boosting the local economies. Apparently, although not stated, both she and the Indian government do not, however, wish to continue the conservation merits of this sustainable use, as there currently is no legal harvest of these nests. It was also noted that BWC does not encourage the consumption of any item of animal origin, however humanely derived.

Humane means to have or show compassion or benevolence, and cruelty is defined as inflicting suffering or inaction towards another’s suffering when a clear remedy is readily available.

The HSI website prominently states that the illegal wildlife trade jeopardizes the survival and welfare of wildlife. It is, therefore, easy to make the case that insisting upon no legal harvest of the nests of edible nest swiftlets in India’s Andaman and Nicobar Islands is both cruel and inhumane and is threatening the survival and welfare of wildlife.

The clear remedy, for which there is scientific evidence, is to allow for sustainable use of this resource. All too often, conservation challenges pit people’s livelihoods against nature. In the case of sustainable use, both nature and people can benefit. Who but anyone who wishes to spit in the face of conservation would insist that poaching and continued declines of this subspecies should persist instead?

Animal welfare is a concern that can be universally addressed in sustainable use programs. Animal rights cannot and only conflicts with proper, effective conservation, condemning nature while in contempt of the people who could effectively benefit from it sustainably.