A short distance from my house in one of Germany’s oldest nature reserves, the ‘Siebengebirge‘-Nature Park, lies a romantic building, the Dragon Castle, a never inhabited chateau with an impressive panoramic view of the Rhine Valley. It wasn’t the Bavarian King Ludwig II who built this copy of his famous Castle Neuschwanstein along the Rhine River, rather it was a speculator from Bonn who erected it in the 1880s after he had made his money on the Suez Canal. It could equally serve as a backdrop for the ‘Dance of the Vampires’ or the ‘Rocky Horror Picture Show’.

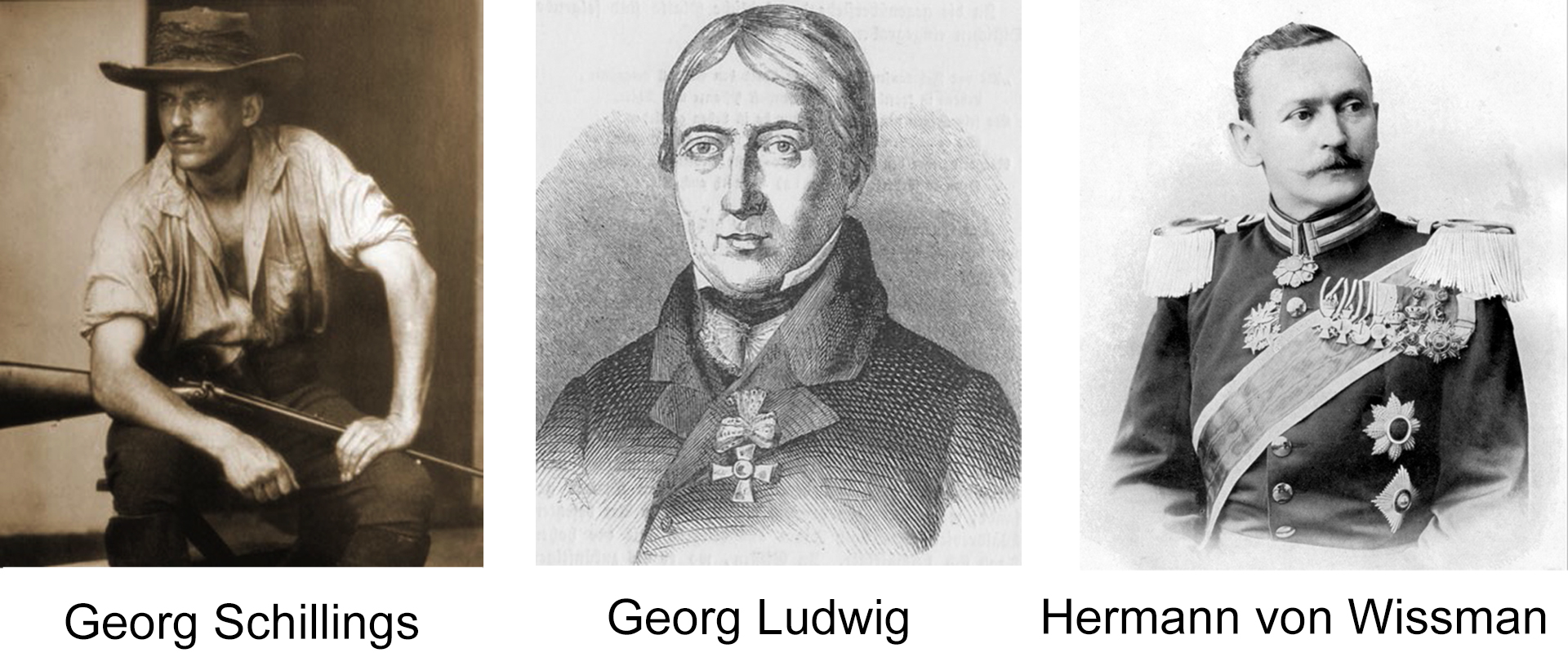

Within the castle complex there is a museum dedicated to the history of nature conservation in Germany. Amazingly, a hunter is among the featured personalities. Carl Georg Schillings (1865 – 1921) is honored for his fight against the killing of herons and birds of paradise in Africa for their ornamental feathers used for foolishly fashionable ladies’ hats of the time. The taxpayer-funded exhibit regretfully mentions that Schillings had also hunted in Africa, but later in life however he became a conservationist. Beside the showcase, somewhat hidden, there is a small plaque which recognizes the animal rights organization PETA as the intellectual heir of Schillings. However, PETA (to quote Dustin Hoffman: “a radical, fascist organization”) has, in contrast to the avid African hunter Schillings, never been famous for its contributions to conservation, but rather more for its unsavory campaigns such as “The Holocaust on YourPlate”.

The green movement is very successful at falsely proclaiming to the public that it invented the terminology and political concepts such as sustainability and conservation. However they denigrate any use of natural resources, which involves hunting and hunters. Therefore, as in the aforementioned case, a hunter who is recognized for achievements in nature conservation must be somehow recast as a non-hunter, if acknowledging him cannot be avoided. Gradually, and with sufficient media repetition, the ideal of green movement achievements becomes standard thought to an urban, uninformed population.

Reality however, is quite the contrary. Six years ago we celebrated the three hundredth anniversary of the so often misused and abused concept of sustainability. Hans von Carlowitz, who came from a family of foresters and hunters, coined the word in 1713 to describe the careful handling of raw materials, especially wood. He used the term for the first time in his book, SylviculturaOeconomica. He called for a “continuous, stable and sustainable use of the forest”. There should be therefore, only as much wood harvested as could re-grow naturally, or through reforestation.

In 1795 the hunter and forest scientist Georg Ludwig Hartig added to the idea of sustainable use in his book ‘AnweisungzurTaxationderForsteoderzurBestimmungdesHolzertragsderWälder’ (Instruction to taxation of forests or how to determine the yield of the timber in forests). The concept was the basis for modern forestry and hunting, and was also an essential component of the report ‘Our Common Future’ by the Brundtland Commission. An oft-quoted definition of sustainable development is defined in this report (1987) as: “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” Five years later the Convention on Biological Diversity was agreed upon at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro and the world’s key document on the future of our globe uses the term sustainable forty times. Whether animal protectionists like it or not the sustainable use of natural resources therein has the same importance as total protection.

Meanwhile this key environmental Convention has been ratified by 196 countries. Thus, sustainable hunting has a firm legal basis, accepted in principle by nearly all countries. Neither unsustainable hunting nor total protectionism has such a basis. We can be proud that it were foresters and hunters who originally developed this concept.

In his two-volume TextbookforHuntersandThoseWho Would LiketoBe,published in 1811 and 1812, Hartig also laid the foundations for modern, sustainable hunting. There he speaks of the “Wildhege,” (Game Management/Wildlife Conservation) which he defines as the “conservation and care of game of every kind”.

Those who study hunting literature of the 19th century find numerous pleas to adopt such game management methods and guidelines. However, it took until the early 20th century before wildlife management in Germany was comprehensively codified in appropriate legislation and the first protected area was created. Amazingly, this process was faster in the former German colonies.

When he was Governor of German East Africa, Hermann von Wissmann, who was also a passionate hunter, issued hunting regulations for the purpose of wildlife management, and created the first modern game reserves in Africa. He founded the Mohoro hunting reserve, which still exists as the Selous Game Reserve. Covering some 50,000 square kilometers it is Africa’s largest nature reserve. Wissmann created the hunting reserves explicitly for the conservation of game species. While he was thinking of nature lovers and hunters of the future, many of his non-hunting colleagues saw the African wilderness as nothing more than a hindrance to progress, and allowed entire regions to be emptied of wild animals.

Wissmann’s name is currently being removed from German street signs that were formerly named in his honor. He is accused by green political activists and left-wing local politicians of having been a colonial criminal. However, there is no factual evidence to back this up. Tanzania showed a better understanding of history when the country, along with the International Council for Game and Wildlife Conservation (CIC), installed a commemorative plaque for Wissmann as the founder of the first modern protected area in Africa at the entrance to the Selous Game Reserve.

Shortly after the turn of the twentieth century the aforementioned Schillings published the following words on the necessity for the protection of wildlife in Africa: “There is only one way to preserve African wildlife in the long term, and that is to place its management and conservation in the hands of hunters.” In Africa’s rich fauna he saw not only a natural monument, but also a resource that could be sustainably utilized for the benefit of local people. Even then there were already “preservationists”, who called for total protection. Being aware of the local conditions, he knew well that total protection achieves the opposite of what is intended, and he spoke out against “excessive demands for mere protection”.

Instead, he wanted to use sustainable trophy hunting to provide an incentive for wildlife conservation and simultaneously to obtain necessary financial resources: “It would undoubtedly be very desirable to bring as many affluent hunting guests into German East Africa as possible. These hunting trips would not only generate substantial revenues by charging for the right to hunt, but also bring large sums of money to the colonies through travel expenses.”

The question remains where the present-day concept of nature conservation (Naturschutz) comes from in the German language and how old it is? Hardly a day goes by that politicians and activists don’t brag that they created the concept, while accusing dissenters of acting against conservation. Regarding the answer to the question, two employees of the Bonn Federal Agency for Nature Conservation, R. Koch and G. Hachmann, have helped considerably. They reviewed literature that has been digitized and concluded that in Germany the term nature conservation in the modern sense was used for the first time in 1871.

Philipp Leopold Martin (1815 – 1885) published a seven-part series of essays on the topic “DasdeutscheReichundderinternationaleThierschutz“. (TheGermanReichandInternationalAnimalProtection). The programmatic essay provides practical guidance for national and international nature conservation and species protection. Whether Martin was a hunter is unknown. However, he worked as a taxidermist and therefore would have at least understood a lot about hunting, and he must have been a friend of the hunt, since his article appeared, hunters will not be surprised, in a hunting magazine. It was called “DerWaidmann:BlätterfürJägerundJagdfreunde.” (TheHunter: PapersforHuntersandFriendsofHunting).

Sources:

Baldus R.D. und Schmitz, W.: (2014) Auf Safari. Legendäre Afrikajäger von Alvensleben bis Zwilling. Stuttgart

Koch R. und Hachmann G. (2011): „Die absolute Notwendigkeit eines derartigen Naturschutzes…“ Philipp Leopold Martin (1885 – 1886): vom Vogelschützer zum Vordenker des nationalen und internationalen Natur- und Artenschutzes. Natur und Landschaft. 86. Jg. Heft 11

Martin P. L. (1871/1872): Das deutsche Reich und der internationale Thierschutz. Der Waidmann. Hefte 1 – 7

Schillings C. G.: (1906) Der Zauber des Elelescho. Leipzig

Schillings C.G.: (1906) With flashlight and rifle, a record of hunting adventures and of studies in wildlife in Equatorial East-Africa. London