Every year, on July 1, one of the United States’ most ingenious, engaging and effective conservation tools is announced – that year’s version of the Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamp, informally known as the duck stamp.

From the 1800s into the early 1900s, American ducks and geese were largely subject to unregulated and unrestricted market hunting.

Top-notch market hunters often set personal goals of shooting 100 ducks per day to fuel the appetites of the increasingly affluent urban populations, insatiably demanding wild game in restaurants and burgeoning towns.

Although the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 eventually brought down such destructive practices, prohibiting the selling of wild birds, and restrictions on non-commercial hunting began to be enacted, a more significant problem loomed large – the rapidly accelerating loss of waterfowl habitat.

Grasslands necessary for nesting were being plowed under for agriculture, particularly wheat production on the Great Plains, an area of the country especially important for producing ducks. Wetlands were being drained to make lands more useful to humans for housing and food production. Within a few short years, these practices had reached massive, widespread levels that, when coupled with severe drought weather patterns, produced soil erosion, dust storms, and ecological devastation on a scale never seen before and hopefully never to be seen again—the infamous Dirty 30s.

In 1934, in response to these Dust Bowl Days and declining bird populations, when no one could deny the glaringly obvious, far-reaching cascades of devastating effects of unsustainable use due to this abuse of land and wildlife, the U.S. Congress passed, and President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) signed the Migratory Bird Hunting Stamp Act.

Those who collect stamps are called philatelists, and FDR was a noted one himself, as he had amassed a collection of over 1.2 million stamps over his lifetime. The Greek origin of the word philatelist comes from loving, fond of, or tending to something without a toll. This refers to the original function of actual postage stamps, where previously the recipient of a letter paid for its delivery, but a stamp meant the sender made the payment. How appropriate, then, to use a stamp (even though the duck stamp is not valid for postage) as a symbolic way of showing that waterfowl hunters (those who love and tend to the resources) paid directly for something they wanted to deliver yet also receive. A legendary and brilliant concept that meshed well with FDR’s conviction that stamps told stories.

Thankfully people in the 1930s were pragmatic and realistic like this. Nowadays, vocal members of the public and government largely or completely out of touch with nature would likely call for a ban on waterfowl hunting if faced with a similar situation – or even if not, if they just simply decided they didn’t like it.

But the good citizens of yesteryear instead took firm and proper actions to fix the problem of habitat loss. All waterfowl hunters older than 16 were and still are required annually to buy and carry a duck stamp. And many pull double duty by purchasing two stamps – one to carry in the field while hunting and one as a keepsake for their collections at home.

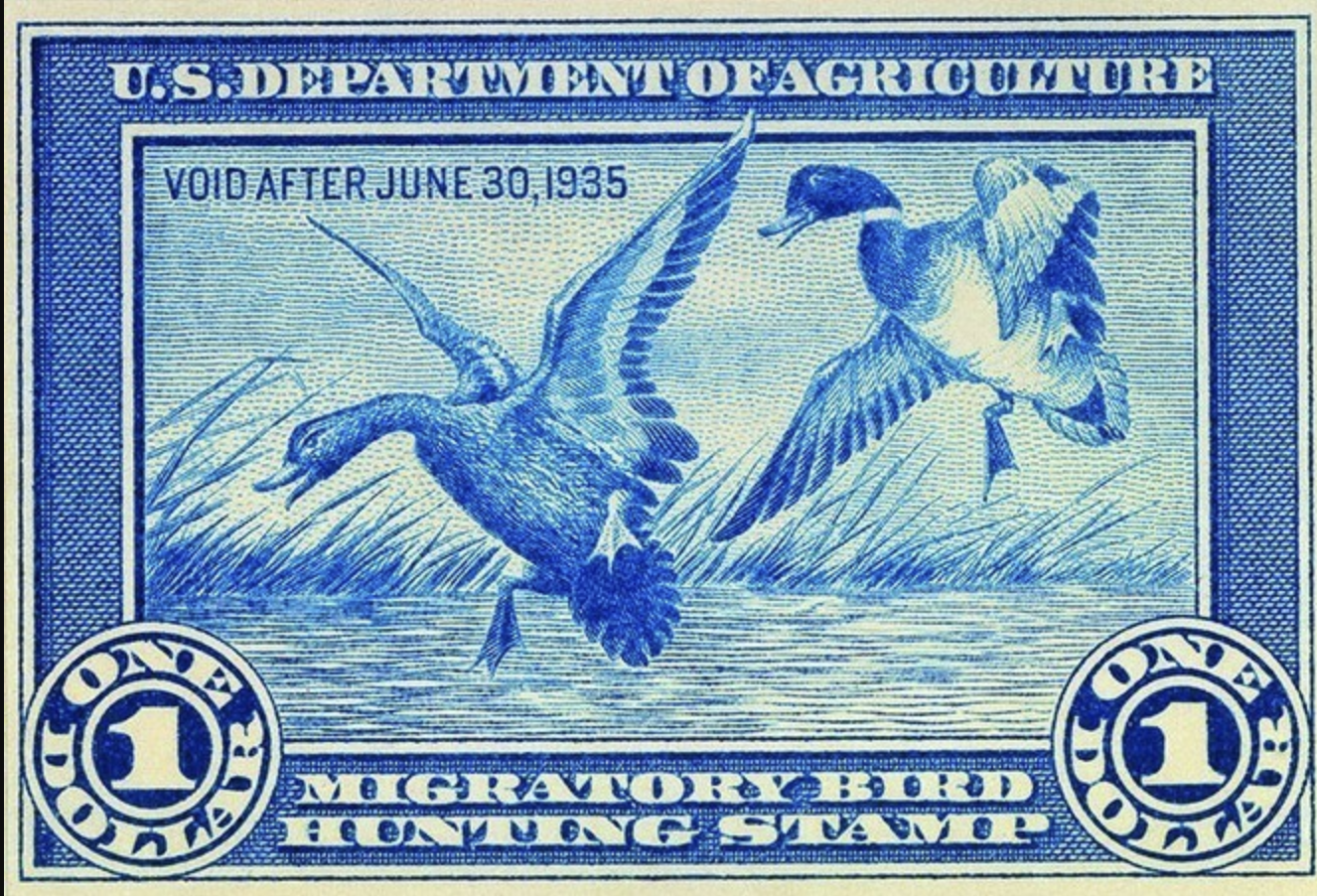

The first duck stamp ever cost USD 1. J.N. “Ding” Darling drew it in 1934, a waterfowl hunter keenly concerned about conservation, a Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist, and then director of the Bureau of Biological Survey, the forerunner of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). In 1949, the duck stamp became an art contest, open to any American citizens older than 18, and it remains the only art competition of its kind sponsored by the U.S. government, open to all. The current price of the duck stamp is USD 25.

Its efficacy is admirable. Since 1934, over USD 950 million has been raised to protect over 6 million acres of habitat. 98% of the revenue from the sale of these stamps goes directly to acquiring, expanding and managing national wildlife refuges, waterfowl production areas, and, more recently, conservation easements on select private lands.

Habitat that not just ducks and geese require, but that flora of all types, and fauna from the smallest of invertebrates on up to the largest of mammals, both resident and migratory, needs, including one-third of the species currently listed as threatened or endangered in the USA. And not only can humans enjoy hunting, birdwatching, nature photography, environmental education, and outdoor recreation on these properties to varying degrees, but humans also benefit from the ecosystem services they provide, such as helping to maintain groundwater supplies, filter pollutants, store flood waters, and protect areas from erosion.

Inarguably, the duck stamp is one of the most successful conservation programs ever initiated. Anywhere. Around 1.5 million are sold yearly, yielding approximately USD 40 million in proceeds. Over 300 national wildlife refuges have been acquired with duck stamp funds, and these refuges exist throughout all fifty states.

Great ideas tend to inspire others, and over 1500 non-federal such stamps have since been issued in many states throughout the union. Plus, in 1989, the USFWS instituted a Junior Duck Stamp contest, connecting art and conservation through environmental education for those under 18. Since 1984, Congress also permitted the Interior Secretary to license the reproduction of duck stamp artwork on products made and sold by the private sector. Royalties accrued go to the fund for wetlands acquisition.

Unsurprisingly, the duck stamp contest is most often won by artists who are avid waterfowl hunters. Who better to portray waterfowl artistically and authentically than those with significant firsthand, in the field experience and direct interest in the proper conservation of these birds and their habitats?

Although anyone can buy duck stamps, which function as passes to any national wildlife refuge that charges an entrance fee, waterfowl hunters are still the primary stakeholders who buy them. Those who utilize these lands for non-hunting outdoor recreation apparently do not feel compelled to voluntarily purchase duck stamps and contribute as much as they should. A study on birdwatchers participating in the National Audubon Society’s annual Christmas Bird Count from 2013 to 2015 revealed that only 20% of these birdwatchers had bought duck stamps. And of that 20%, 40% were waterfowl hunters.

In order to sustainably, and consumptively use any renewable natural resource, one must continue to produce that resource. In the case of wildlife, that means protecting and properly conserving the required habitat. In America, the duck stamp program, funded and proudly endorsed by waterfowl hunters, is a commendable story that any stamp could ever tell. Well done, FDR, for having the foresight to put his philatelist ideals to pragmatic conservation use.