The tsetse fly (Glossina sp.) carries the Trypanosoma parasite, which causes sleeping sickness in humans and nagana in domestic animals, particularly cattle.

In the early 20th century, much of Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) was being opened up for cattle ranching.

Eliminating the threat of the disease was deemed essential for the development of the country.

In his annual report on tsetse fly control in the country in 1949, J.A. Whellan, an entomologist with the Department of Agriculture, noted:

“For the control of Glossina morsitans in Southern Rhodesia, controlled discriminate game destruction has been carried out since 1925.

By this method, the larger game animals, on which alone G. morsitans can thrive, are so reduced in numbers in a belt (usually about twenty miles wide) along the boundary of infestation that the Tsetse can no longer survive, because it is unable to obtain meals with sufficient dependability and regularity.

Thus, the fly, in effect, retreats. The barrier belt is then pushed forward by about half its depth, and the Tsetse is driven in turn from this new belt. This process can be repeated.

A fundamental feature of this type of control is that no attempt is made to reclaim land unless it is required for settlement and development.

There are two main reasons for this.

One is that it is desired to keep the number of game animals necessarily destroyed as low as possible.

The other reason is that sufficiently close settlement of land, if the land can continue to support such settlement, is, of itself, an excellent barrier to the renewed spread of Tsetse.

The present position is that the barrier belts have been kept stationary since 1940 and are used to prevent a renewed advance of fly into country already reclaimed.”

He continues later in his report to give the number of head of game destroyed that year.

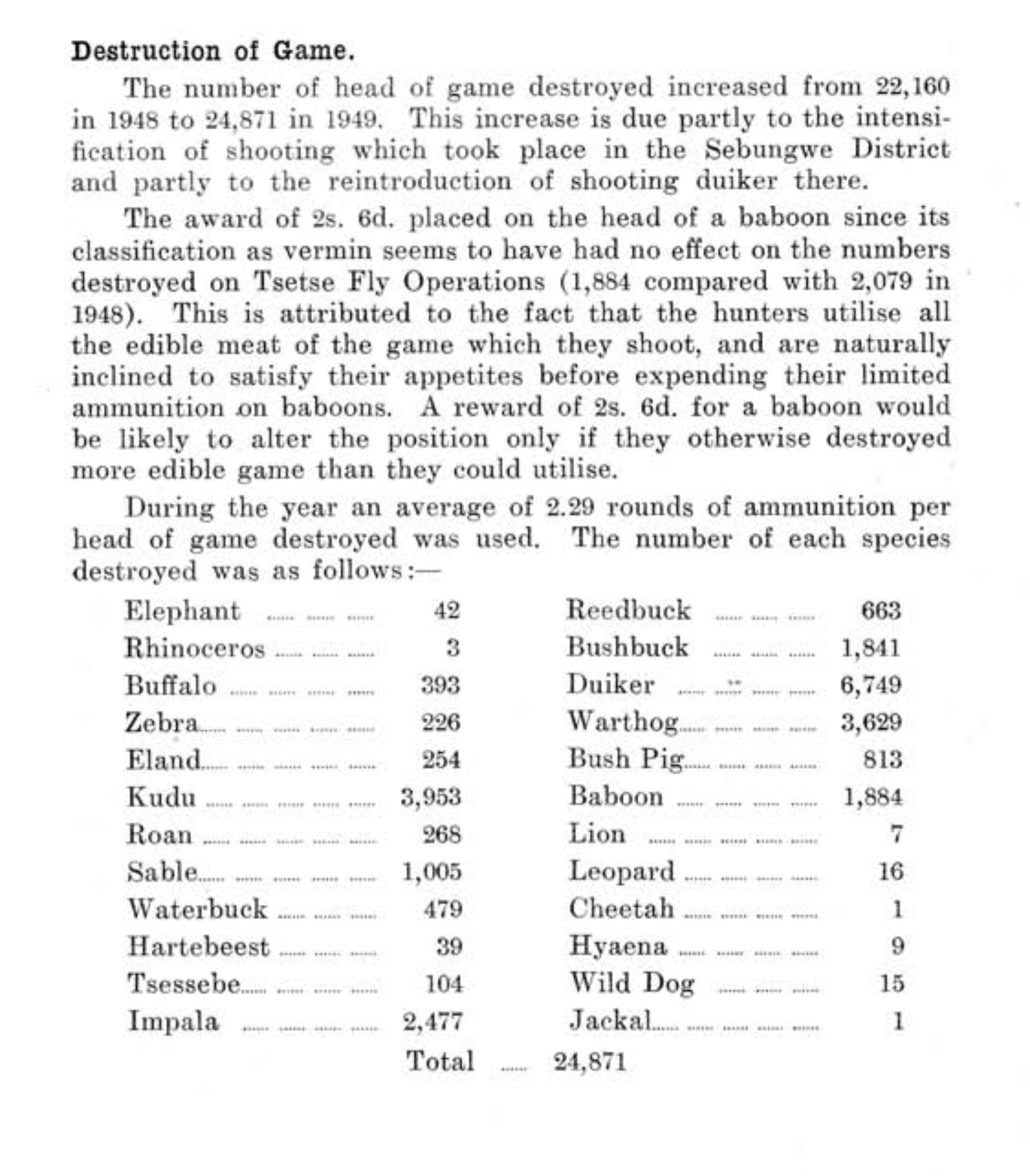

“The number of head of game destroyed increased from 22 160 in 1948 to 24 871 in 1949.

This increase is due partly to the intensification of shooting which took place in the Sebungwe District and partly due to the reintroduction of shooting duiker there.

The award of 2s. 6d. placed on the head of a baboon since its classification as vermin seems to have had no effect on the numbers destroyed on Tsetse Fly Operations (1 884 compared with 2 079 in 1948).

This is attributed to the fact that the hunters utilize all of the edible meat of the game which they shoot and are naturally inclined to satisfy their appetites before expending their limited ammunition on baboons.

A reward of 2s. 6d. for a baboon would be likely to alter the position only if they otherwise destroyed more edible game than they could utilize.

During the year an average of 2.29 rounds of ammunition per head of game destroyed was used.”

He goes on to give a list of the species and number of each shot that year (see attached photo).

Between 1933 and 1958, over 148 00 wild animals from 36 different species were shot, including 208 black rhinos.

Ultimately the policy was a failure.

In 1959 the strategy moved away from wildlife annihilation towards the destruction of tsetse fly habitat, which was, arguably, even more devastating.

Eventually, the aerial spraying of DDT and the use of insecticides and traps brought the fly under control over most of the country.

During the building of the Kariba dam on the Zambezi River in the 1950’s an operation was undertaken to save animals in the Zambezi Valley from drowning in the rising waters.

Operation Noah saw 5,274 animals captured, with a net 4,129 being saved, nearly 50% of which were the ubiquitous impala.

This number is a mere fraction of the amount shot during the tsetse fly eradication program.